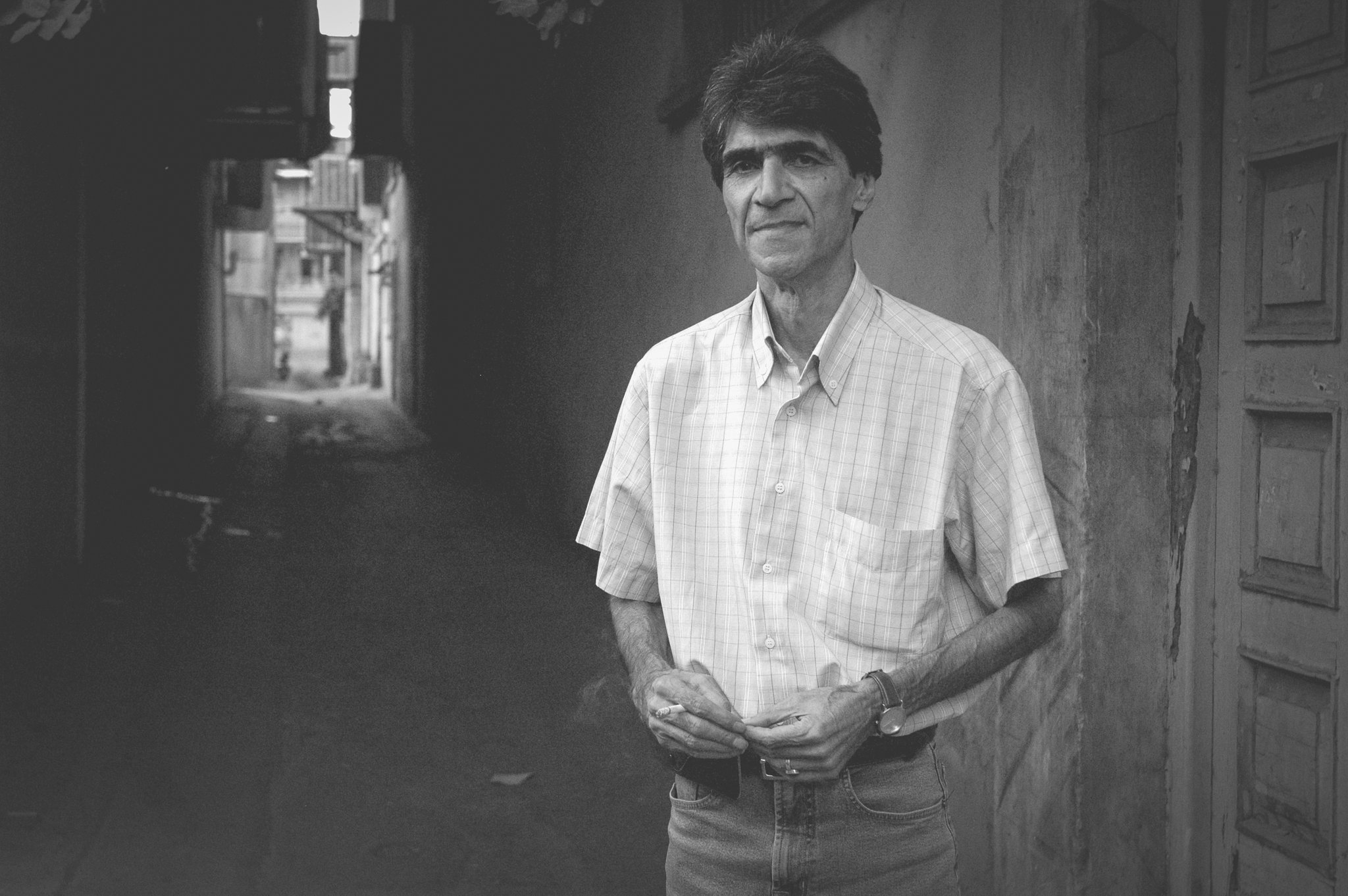

Iranian film director and writer Nasser Taghvai passed away on October 14 at the age of 84. For the past 24 years, he had not been allowed to make a film – and yet he remains one of Iran’s most influential artists.

By Omid Rezaee

To write about the dead is to walk on the edge of a blade. Every obituary about an artist risks falling into sentimental pathos – into a tearful elegy that clouds insight rather than bringing it. When print journalism still thrived, the obituary of a famous person was considered a literary genre of its own. It was taught in seminars, practiced with discipline and care. In those “censorship-free societies,” as Nasser Taghvai used to call them, there were journalists who spent their lives writing about the deaths of great minds – and earned both reputation and livelihood through it.

But no one teaches how to write about the death of a man whose unmade works outnumber the completed ones; whose films and writings – both before and after the catastrophic revolution of 1979 – were sliced apart by the scalpel of censorship.

On social media, Taghvai was not merely mourned; he was celebrated. Celebrated for his No – for his unwavering refusal to compromise with power. Quotes from old interviews resurfaced and spread:

“As long as one needs permission to make a film, I will make none.”

“As long as someone must read my script before filming, I will not shoot.”

“When they don’t let you film, occupy yourself with something else – to preserve the dignity of your art.”

He kept his word. Many others said similar things – and then went on filming, publishing, compromising. Taghvai did not. Until the very end, he stood by his refusal. He never made another film, never submitted a manuscript for approval.

I last saw him in the winter of 2018, in Munich. An Iranian festival was showing a small retrospective of his films. He was frail; illness had left its mark. His eyes were weary, his voice carried the weight of years. Later, his relatives told me he had been lured to Germany with empty promises – that a film museum wanted to restore his work. But the festival’s organizers seemed more interested in the aura of his name than in him as a person. Still, he came. He attended the screenings of Tranquility in the Presence of Others (1972) and O, Iran, spoke briefly, even smiled. The theatres were small but full; and when he looked into the audience, there was still a spark of the old fire. It is a sad truth that one of his last public appearances – before illness and isolation – took place not in Tehran or his hometown Abadan, but in Munich.

I accompanied him for a few days and recorded what would later become his final published interview. I asked whether doing nothing was truly a way to preserve the dignity of art. Whether his silence didn’t leave the stage to those who neither understood cinema nor felt responsible toward society. I expected a philosophical, political answer. But Taghvai stayed grounded:

“That’s the reality of our country. We’re censored before we even start shooting. Under such conditions, one can only make shallow films – imprecise films. That would be a waste of the people’s money.”

For the then 76-year-old director, whose last released film was seventeen years behind him, precision was reason enough to stop working.

To write about deceased artists also means to honour their works, to trace how they shaped culture and society. But one doesn’t even need to turn to Taghvai’s unfinished or unpublished projects to realize that he – and others like him – fit into none of the theories born of censorship-free journalism. His first feature film, Tranquility in the Presence of Others, languished for four years in the drawers of the censors. Had it been released on time, it might have helped define the Iranian New Wave. When it was finally screened, briefly, the movement was already underway – and Taghvai’s influence smaller than it could have been.

The same could be said of his literary work. The critic Safdar Taghizadeh, who recognized Taghvai’s talent early on, wrote in 2021 that he had “instinctively used modern narrative techniques at a time when most Iranian writers drowned their stories in adjectives and ornament.” His prose – terse, lucid – might have transformed Persian storytelling, had his first collection The Summer of That Year not been banned after its initial publication.

Taghvai was among the few Iranian filmmakers who came from literature – and had already succeeded there. He insisted that he had never left writing behind, that screenwriting was simply its continuation: “To make a film, you need a good story – and you must know language.” Still, he published only that one collection of short stories, banned after its first edition and never reprinted. His later manuscripts he didn’t even bother to submit to the censorship office.

He discovered the camera in the early 1960s, during a journey to the ports and islands of southern Iran with writer and dramatist Gholamhossein Saedi. Instead of taking a secure job at the Oil Company, he went to Tehran to work in Ebrahim Golestan’s film studio – as an assistant, a tripod carrier, a learner. Later he made documentaries for state television. When I asked why he chose television – so despised among intellectuals as a “medium of stupefaction” – he simply said: “Because the director, Reza Ghotbi, was an educated, liberal man. Maybe even a bit of a dissident.”

Taghvai believed in the magic of cinema so deeply that he once said, “Cinema was invented a second time in Iran.” For him, film was the new poem – a vessel for centuries of repression, loss, and endurance.

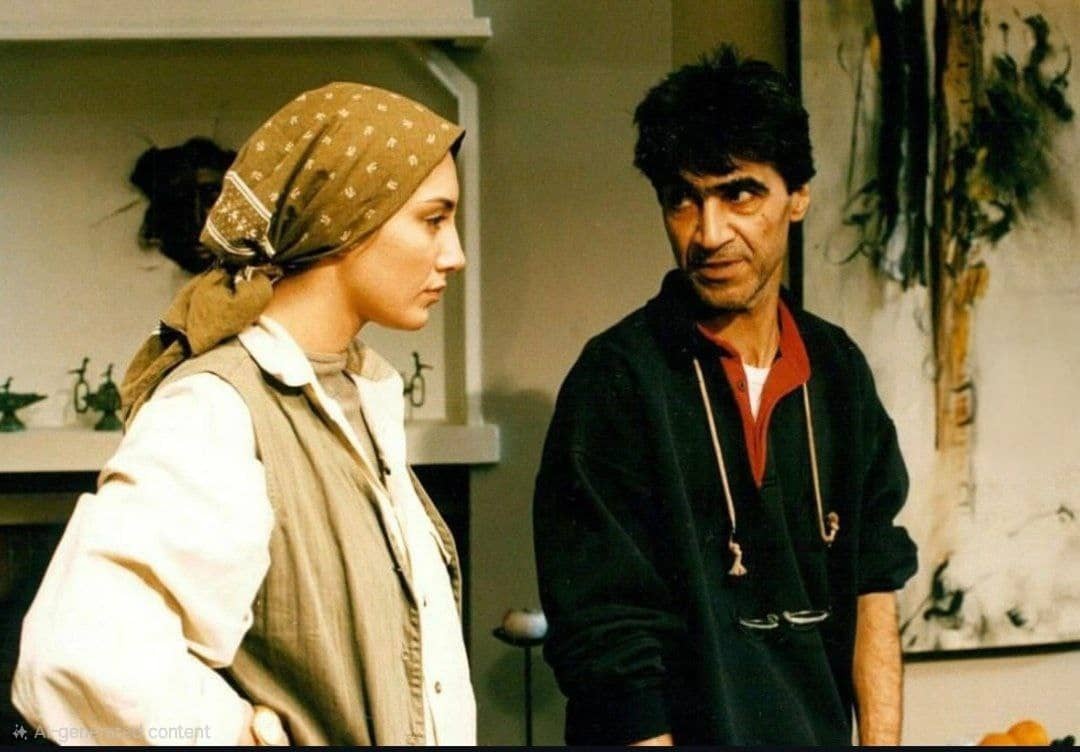

Like Dariush Mehrjui, Taghvai was a master of literary adaptation: Tranquility in the Presence of Others after Saedi, The Curse (1973) from a Finnish story, Captain Khorshid loosely after Hemingway, My Uncle Napoleon from Iraj Pezeshkzad’s novel, Kuchak-e Jangali from a book about the revolutionary Mirza Kuchak Khan.

Yet the phrase that recurs most in the chronicle of his life is: “Attempt to make a film.” The list of projects he was prevented from completing is far longer than the six feature films he finished. After Unruled Paper (2001), he wanted to shoot Zangi and Rumi – about the First World War. Filming began, but authorities halted it. Another project, The Bitter Tea, about the rape of an Iranian woman by an Iraqi soldier, was banned for “moral reasons.” And Kuchak-e Jangali, already in production, was taken from him; Behruz Afkhami – later a mouthpiece of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda – replaced him and shot a rewritten version.

Taghvai often said: “In societies of censorship, artists must be judged by what they were not allowed to create, and by the words they were never permitted to say.”

To understand Taghvai, one must read between the lines of Unruled Paper, Captain Khorshid (1987), and O, Iran (1990) – and also know what, and who, stopped him. His No was not an act of heroism but of self-defence. He was no martyr seeking silence, but an artist deprived of speech. In a country where paralysis is often mistaken for virtue, Taghvai was the opposite: a restless spirit who worked by staying silent – and fought by not yielding.

He felt a deep kinship with the one-armed Captain Khorshid, the protagonist of what may be his greatest film.

“I identified with that man,” he told me. “His struggle against oppression, his fight to survive – that was my struggle too.”

I asked, almost challengingly: But that man’s fate was death. Isn’t that the ultimate defeat? Aren’t we all, in the end, defeated by life?

He replied: “I don’t call death a defeat. Death is part of the struggle.”

And perhaps that is the most honest definition of art in a country that wages war against its artists.

Photo: Hamid Janipour

The original Persian version of this obituary appeared on the Aasoo platform.